Film As The Perpetuation Of Consumerist Mentality

Of all arts, film is one of the closest to the center of the Digital Era storm today. Everything from making to watching a movie is rapidly changing. We have been witnessing the decline of video rental stores and film stock and the rise of streaming sites in a matter of a few years. And now people wonder if movie theaters could be next in line to disappear.

Those ongoing changes are shaking up the Hollywood industry, as well as new distribution networks, independent filmmakers, and ourselves, the viewers. And while they fight each other for our attention and search for entertainment, intimate links with consumerism unfold.

Cinema has nine lives

Hollywood executives are alarmed by recent box office results. So much so that, over the last few years, they have been digging out 3D film and opening Imax theaters to try to appeal to audiences and make sure movie watching is not restricted to TV sets or computers. But this is not the first time the film industry has to struggle to remain relevant. And when it does face a battle, it resorts not only to high tech, but also to themes that sometimes lead to new experiences, other times just to old formulas.

The Girl Can’t Help It (1956), for example, used colors and explored screen sizes, as well as Little Richard’s rock ‘n’ roll and Jayne Mansfield’s body, to compete with the appeals of the then new color TV.

In 2013, in his , Steven Soderbergh told a story about a flight where a man was watching movies in front of him, and how amazed he was at what he saw: the guy was skipping over all the narrative and just watching the action sequences. Soderbergh then went on to comment on what he has been witnessing in the industry he works in:

“There are fewer and fewer executives who are in the business because they love movies, there are fewer and fewer executives that know movies.”

Soderbergh uses his account of that antsy viewer as an anecdote to describe how test screenings and high operating costs are leading Hollywood to risk less and make safer bets in sequels, remakes, and adaptations.

He goes through today’s film economy: how 50% of American blockbusters’ takings are coming from the international market, how producers have been looking to make simpler stories and remove all ambiguity, how they are relying on a the-more-superficial-the-more-universal mindset.

Summing up: a movie is made on an industrial scale, targeting the masses, and screened for standardized, disposable consumption. How far can the industry go to hold on to its profits? How similar is a movie to a piece of fast fashion?

When the trailer is better than the movie

If that is the state of cinema in Los Angeles’ meeting rooms, that didn’t just happen by chance. On this side of the scope, at shopping malls and our homes, it’s a reality that is increasingly resonating.

In 2013, Clay Johnson launched The Information Diet, a book advocating for more conscious information consumption. Johnson states that, with so much information being thrown at us all the time, we must learn to better select the things we are going to expose ourselves to.

Making a connection with the state of cinema is automatic. The sheer number of movies released every weekend and the swiftness of how they start and stop showing in theaters make it impossible for the viewers and the media to have enough time to process the meaning of each story, because the next must-see is already about to premiere.

This fast consumption-based world is described by Jonathan Crary in his 2014 book Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. His words can easily resonate with that movie fan Soderbergh saw on a flight:

“The only consistent factor connecting the otherwise desultory succession of consumer products and services is the intensifying integration of one’s time and activity into the parameters of electronic exchange. Billions of dollars are spent every year researching how to reduce decision-making time, how to eliminate the useless time of reflection and contemplation.”

More than just a marketing plan forged by executives, the effects of film consumerism are part of a behavior setting. Just think about how easy it is to get, legally or illegally, more movies than we can possibly watch.

Just think about how quality is not nearly as important as quantity when we watch, on our phones, movies that were shot with high-tech equipment.

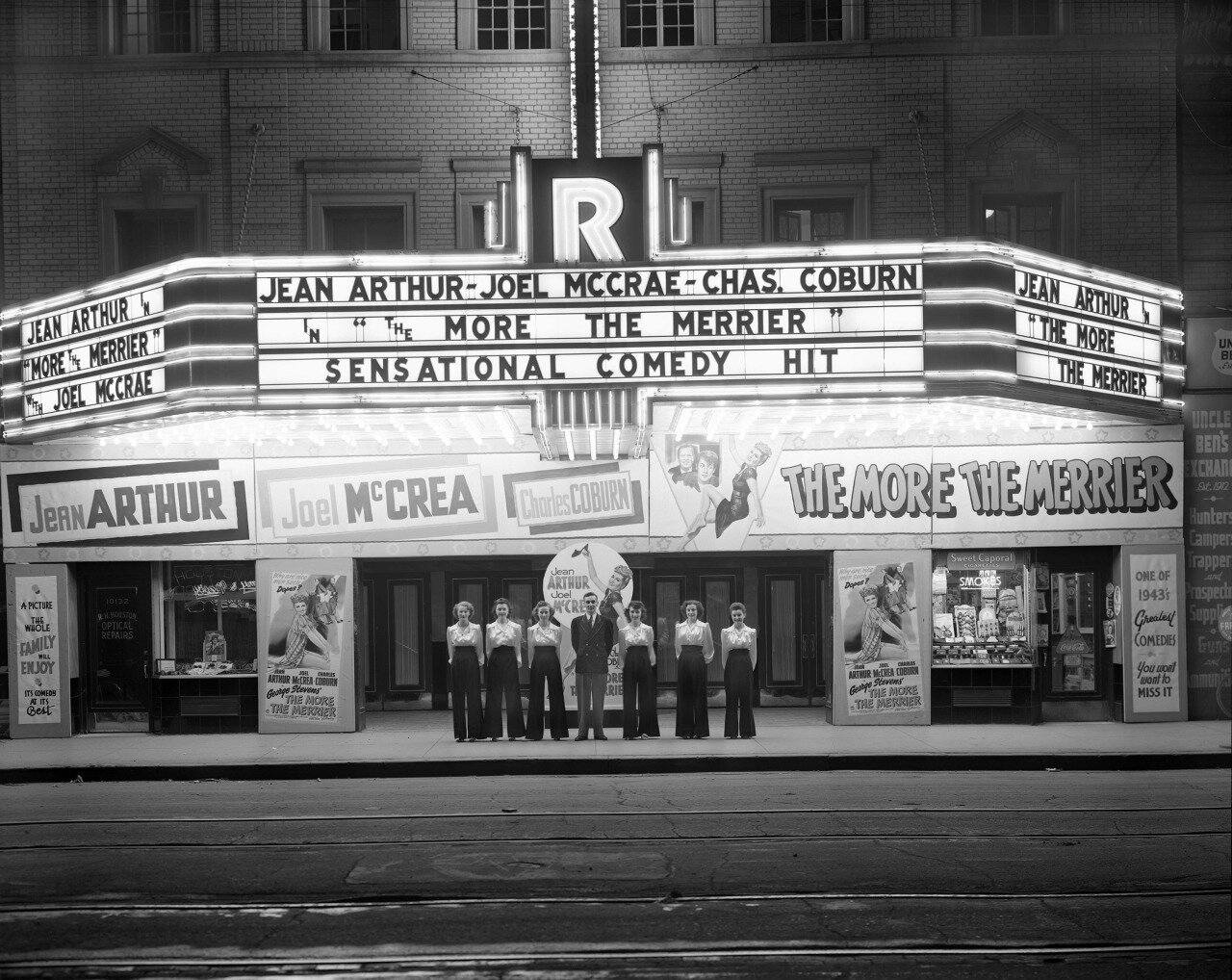

Just think about how that ritual of going into a big dark room and being completely immersed in a communal show is now going through a crisis.

State v. Potential

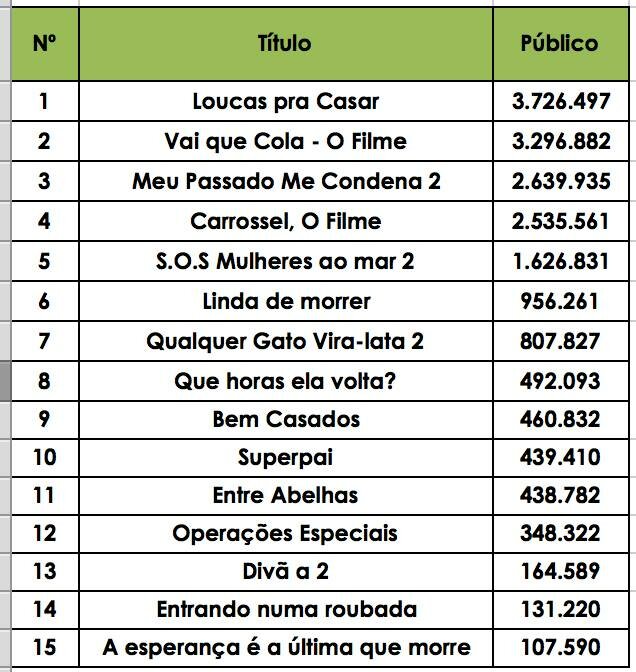

Although it hasn’t been mentioned here yet, Brazil’s film industry is also facing those same paradigms. Not only are our theaters virtually taken over by American movies, Brazilian box office results for its most profitable films in 2015 illustrate just how producers in the country have been clinging to blue comedy plots.

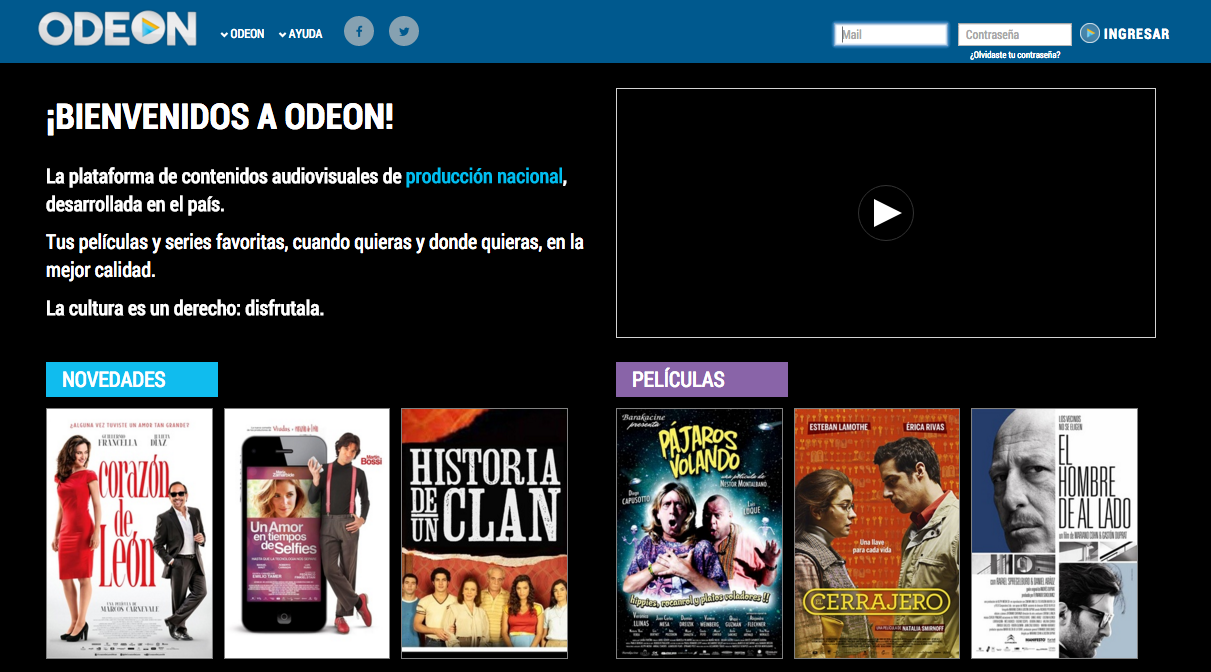

While being more aware of our consumerist mentality is bringing out new alternatives, like appreciating local production, accepting multiple identities, embracing the sharing economy, how does that work when it comes to cinema?

It’s true, digitalization has opened up new channels and possibilities, but we are still driven to watching the same movies and the same TV or Netflix shows (and by the way, despite offering more diverse, complex content, aren’t they being watched with the same consumerist intensity?).

Discussing the paths cinema has taken is not about feeling nostalgic for the old theater format. It’s about questioning what we could take from the film experience if financial return were not top priority and if our journey in front of the screen (big or small) could go beyond the logic of consuming.

In his text Utopian Film, author Alain de Botton goes back to Ancient Greece to point out the potential of film:

“It comes from the Ancient Greeks who brought maturity to the predecessor of cinema: theater. Fascinatingly, they didn’t just file going to the theater under ‘entertainment’ and leave it at that. They thought very deeply about what the point of sitting in a theater might be and concluded that it should be a therapeía, a resource to help us grow into better, wiser, more mature kinds of people. It belonged, together with religion and philosophy, to the forces that could develop our souls.”

The truth is, the present has a potential for creative, venturesome experimentation. There is a slew of paths available, as we can see in three remarkable films that were recently released: Sean Baker’s Tangerine was completely shot with smartphone cameras; Quentin Tarantino shot Hateful Eight in the old 70mm format; and Gaspar Noé’s Love used 3D to go on a lysergic love journey.

Consumerist mentality is deeply rooted to the point that sometimes it just seems natural. It’s not always easy to realize that the way we watch or don’t watch a movie is intimately connected with the emergencies of today’s world.

Comment